English Patient in Ecuador

Blimey! Did you know Jon's New Zealand book Squashed Possums is out now - find out more

Do you want to get away from the tired tourist sites? Get a different perspective on a place? Then why not experience a country's health service by impressively smashing yourself up in some terrible accident? No? Don't fancy it? I didn't think so. But having done just this, I thought I'd share my experience, at least so you don't have to.

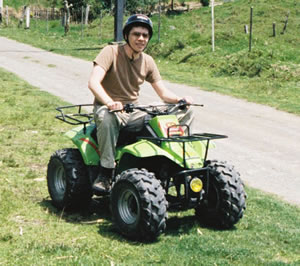

Crashing and somersaulting head first over the handlebars of a quad bike isn't amongst the smartest things I've ever done. But then hurtling face first into a gravel track and running myself over didn't improve matters either. What was I to do? I had seen the ridge in the middle of the road and seen it coming at me as I rounded the corner, but there just wasn't time. In a disorientating moment I was tangled amongst the fast moving machinery as the bike performed a grotesque dance around me. I blacked out. When I came to, the bike had dragged me 30 feet down the road before coming to an abrupt halt, upside down in a ditch.

Crashing and somersaulting head first over the handlebars of a quad bike isn't amongst the smartest things I've ever done. But then hurtling face first into a gravel track and running myself over didn't improve matters either. What was I to do? I had seen the ridge in the middle of the road and seen it coming at me as I rounded the corner, but there just wasn't time. In a disorientating moment I was tangled amongst the fast moving machinery as the bike performed a grotesque dance around me. I blacked out. When I came to, the bike had dragged me 30 feet down the road before coming to an abrupt halt, upside down in a ditch.

I tried to get to my feet but quickly collapsed. I was hurt - my left hand lacerated with deep bloody scratches. My face was bloody and raw. Trust me, never exfoliate your face at high speed on a gravel track whilst freewheeling down a volcano on a quad bike. It's messy and really quite unhygienic.

I sat there in shock, as a pair of Ecuadorian octogenarians interrupted their afternoon stroll with a concerned "com estas?" I couldn't remember enough Spanish to give an honest answer, so instead I improvised with an unconvincing "Estoy bien."

Before long I was cleaning my wounds under a hot shower back at the hostel. To my relief, a rush of endorphins swamped my system as I plucked the gravel and dead flesh from the open wound below my knee. My leg looked like it has been attacked by a lunatic armed with an ice cream scoop. My friend, Jorik, treats my wounds. The pain is excruciating and the room must look something like a torture scene. Playing the role of the mad doctor, he politely asks to spray my open wounds with medicinal alcohol. The pain is beyond words as we collapse into hysterical laughter.

The following day passed with little to distinguish it. But what I didn't immediately do was visit a doctor.

Why? It's hard to say. Was it the good old stiff upper lip? A little. Was I in denial over the state of my injuries? Perhaps. Was it a fear of Ecuador's medicinal services? Absolutely.

What happened later that afternoon, some might attribute to fate, God, or a guardian angel. I don't, although perhaps I should.

"Can I interest you boys in some nice fresh coffee? Not Nescafe," she insisted. The woman had a thick German accent. A big lady, she looked like she'd served some hard time in a bakery. "Hey, what happened to your face?" she enquired. With heavy bandaging and a precarious limp my injuries were all too apparent. I explained what had happened. "They're blo*dy dangerous those things," she explained, rather unnecessarily. "A kid the other day, he tried to run a police road block. Crashed his quad bike and took his head clean off." Gulp. She wasn't impressed that I hadn't seen a doctor. "You're too young to lose your looks and you don't want scars. There's a clinic just down the next road - you should go..."

What was I doing? I must have been clear out of my mind not to see a doctor! I thanked her and before I knew it I was expressed past the queue of the local clinic and was flat out on a coach. My doctor was Russian and didn't speak English. We skip Spanish and instead communicate in broken German through my Dutch friend, Jorik. "He says your wounds are infected and you need, uh, what is the word?" Ouch! I get the gist as the doctor stabs another anti-inflammatory into my infected face. I stare at the ceiling and try not to watch. I'm utterly helpless as the doctor quietly stitches my wounds with a thick black thread, more like bootlace than something you should find in an operating room.

With some relief, we returned to the Secret Garden in Quito. The family run hostel was to become a home from home during my convalescence. In such a short time, these strangers, my hosts and fellow travellers donated medication, offered advice, sympathy and a steady pair of hands to cleanse my wounds. I don't know what I would have done without them and was rather touched when Maya nicknamed me the 'The English Patient'. Hang on though, didn't he die?

With my chances of hiking the Andes scuppered, the closest I got was a trip to the Vos Andes hospital to get my stitches removed. The hospital was smart, clean and modern and I was seen within minutes of arrival. It was, by all accounts, not what I expected and exceeded my expectations of an NHS hospital. The public health service in Ecuador has plenty of horror stories - dirty needles, wrong injections and diseased wards. But then, there are the privately funded clinics where a ten dollar bill will buy you a prompt appointment with a professional consultant. It doesn't seem like a lot of money, but alas, given the collapsing economy in Ecuador, such treatment is now a luxury that many cannot afford. Quito's traffic lights are filled with casualties busking a living. One juggles fire-sticks. Another has a pair of shop front mannequins strapped to him for an impromptu piece of theatre. One amputee drags himself around on wheels and wears a bright yellow and orange cowboy suit.

It just goes to show, it always pays to have travel insurance.

Blimey! Did you know Jon's New Zealand book Squashed Possums is out now - find out more

28/02/2008

Latest articles

- Shanghai shopping

Shanghai is changing fast. - Beijing tea house scam

Getting conned, scammed and done over in Tiananmen Square - Beijing Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)

Brief introduction to Chinese television, the 'Weather Modification Office' and how China views Taiwan...